Today I am two weeks post-vaccination for COVID-19. I went out into the back yard to take a new maskless selfie for my FB page.

I'll still be wearing one quite a bit for a while, indoors in public or with unvaccinated friends at least, while we all navigate through this in-between time. I'll keep them around for when I have respiratory symptoms, for sure. But I felt like marking the milestone some way.

+ + +

I'm planning on going to Mass this weekend. (How odd to be writing that sentence!) Just me, by myself; both Mark and I feel like starting off with relatively uncrowded spaces if we can. My solution is to go early: I signed up to go to the 7:30 a.m. Sunday Mass at our own parish. Mark is not such an early bird; he may try a weekday Mass first, or a smaller congregation nearer our house. We'll probably take turns until we decide it's prudent to bring the children.

+ + +

Last Sunday, the Gospel—on the parish livestream—was "I am the vine, you are the branches." It's tempting to think of returning to Mass as a sort of re-attachment, but that is stretching the metaphor too far. I have not been utterly cut off from the vine. I have had regular, if infrequent, access to the sacraments. I have maintained a prayer life that's maybe been even more lively, on average, than before. I have been part of the great mass of Christians, friends and strangers, praying for one another for intentions small, large and unknown; I've studied, even co-hosted a little book group for the end of Lent and the start of Easter.

I'm still here, as are many others who always have been attached: the tendrils of the true vine are invisible. Did we forget? There always, always, always have been people for whom attending Mass in person, often or ever, is imprudent or impossible. And yet they are infused with the green life, whether we remember them or not. Now that I've been one of them, let me not forget again.

What will it be like to return? Jesus is the same. I'm changed. Something has sharpened in me.

+ + +

Aloneness, and media, provides a lot of opportunity for intercessory prayer. I mean, a lot. And I know I haven't taken all the opportunities there have been. But… so much suffering happened over the last year-and-then-some, and so much more came to light. A great deal of cruelty and selfishness was exposed. And maybe more than this, a great deal of carelessness: a kind of breaking and spilling and muddying, and wandering off without thinking, probably across the clean floor with muddy shoes, never noticing, never taking note later that someone has come by and cut themselves on the shards, and a someone else has come by and cleaned up the mess. Unintentional, to be sure. But somewhere there's a willfulness not to look behind you. And when you really see that carelessness, the carelessness of people who do not seem to see how careless they are (and yet… how could it not be obvious?) you realize that yes, you also must have been this careless, at least a little, and how often? How would you know how many messes you have made when it is someone else's role to clean them up?

So, a lot of penitential prayer as well.

+ + +

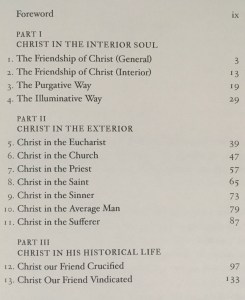

MrsDarwin and I hosted, as I mentioned, a brief book club on Robert Hugh Benson's The Friendship of Christ. (Buy her edited, prefaced, and newly-typeset paperback edition here.) It was a good book for a strange time. Different people got different things out of it, for sure. Here's what it did to me: I opened it thinking "Perhaps this will tell me how to get closer to Jesus," and found that—for me—it really has been a matter of appreciating how close He has come to me already. I mean, He's right there. All the time. No, really, right there. Right here.

Even things that I thought were a way of holding Him at a distance are means by which He comes very, very close. I know that more than I did before, and really believe it.

+ + +

All of a sudden, I started to find anything that smacks of purity….

UNBELIEVABLY tiresome.

I don't mean the virtues that include the term "purity," although the word used all by itself, well, its attributes should be broken up and assigned to other virtues. Ninety percent of the time when Catholics start talking about the virtue of purity, they are really just trying to avoid speaking frankly about sex, and it drives me up the wall. No, I mean purity like… this fear of contamination? This fear of going out to the margins, of exploring the distinctions, of making contact?

I've been a practicing, communing Catholic since I was eighteen. I had to figure out the culture gradually, as a sort of teenage immigrant to it. Am still figuring it out, as I continue to encounter the astonishing diversity of thought and experiences that makes it up, has made it up, across the centuries and nations, so that it's more like cultures than culture. And I'm sure a lot of my memories of the process of figuring it out have been colored by all kinds of cognitive biases. I started out with a longing to belong, trying to understand what it meant to be part of a larger community of believers, and trying out the different kinds of "belonging" that there are. We do things this way here. If you are Catholic, you will be a certain way. I have tried to do things this way, and that way, and other ways, to see which ways fit, to see how to belong.

But all belonging means a definition of "self" and "others"—of "us" and "them—and more and more I am convinced that the "us" and "them" is and always has been an illusion. There are ridiculous "us/them"s within the Church as well. But it isn't real. There is no us and them, there is only everybody: trying or not trying, or trying to some degree, to align themselves with the way and the truth and the life, which presses us invisibly from all around. Our job is to align ourselves and in so doing, strengthen the field, so to speak, and just doing that for real helps align others.

Be not conformed to this world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind.

Yes, yes, baptism is real and a maker of an "us," but nobody is excluded from it in principle; it's a difference in marking, not an essence. We need collective humility, very badly. We could use a little less fear that the Church will come crashing down if we have frank conversations with the wrong kind of people. We could use a little less fear of doing love wrong by sending the wrong message. We could use a little less gatekeeping; the gates will not prevail, after all, no? Caretakers of the deposit of faith have been provided for us, thank God: but lately I've become very aware of the large number of, shall we say, volunteers who have decided it is their job to staff the gates.

The pandemic found me doing a lot of "well, if I was in charge I'd do things a lot differently" and at one point it occurred to me that I am not in charge, and I didn't really want to be. In fact I'm not in charge of anyone, with the possible exception of my own children, and there are signifcant limits to that. I am my brother's keeper, but not his gatekeeper.

+ + +

When I come back, I come back changed. I come back more aware of a certain awarelessness that will probably follow me my whole life. I come back more aware of the closeness of Jesus. I come back tired of separations. I love orthodoxy, orthopraxy, and always have; I've often felt a little ashamed of that, from the pressure of the personal-relationship-with-Jesus crowd; but I've learned that these are not things that stand between us and that relationship; they are a way He befriends us. What has sharpened for me is a new desire for a Jesus-first orthodoxy, a Jesus-centered orthopraxy. I come back seeking to strengthen it.