For a couple of years, 2008 or so, I wrote frequently about exercise and eating strategies. Sometimes I wrote about how those intersect with theology of the body, or Thomist morality. I returned to the topic sporadically, but not steadily, since then. It's been a while since I've written much.

I wrote all that because I was in the midst of two major life changes.

- First, that year when my third child was a toddler, I was prioritizing regular exercise for me for the first time. Having taken lessons before that pregnancy, afterwards I started swimming twice a week, later adding running. In order to keep it up, I thought, I had to be obsessive and inflexible; for better or worse, I was obsessive and inflexible, and I did keep it up. Still am doing it today.

- Later, after the shock of having sustained this new habit for several months, I began restricting calories, and over the course of about six months I lost 27 percent of my initial body weight. Having thought of myself as perpetually dumpy and sedentary since childhood, I found myself now active, and also, not fat.

Note the causality: My writing about this didn't bring it about. I wrote because I was having what I called success, and I was desperately trying to make sense of it. I needed to understand why it was happening, was because I was afraid that if I didn't figure out why it was happening, I would not be able to keep from going back to "the way I was before."

+ + +

Ha. As if I could slip back accidentally to "the way I was before." Back to my early thirties? I am older! Human beings are not reversible. For one thing, my windows of possibility have shifted. For another, I understand more.

I've learned that the effort required to track calories closely enough to override the body's own cues is seriously intensive, tends to push out other satisfying activities, and requires a constant input of motivation. And I've learned that I don't want to live in that kind of monomaniacal relationship with myself.

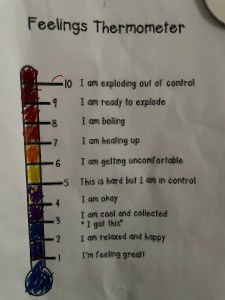

It may seem odd, but motivation itself is part of the problem. I do lift myself up with messages that are true and encouraging, and celebrate with rewards that are both pleasant and good. That's great when they work. But if those don't do the job, I've often been tempted to use any mental means to the end of self-control: shame, fear, dwelling on bad memories, threats of self-punishment; contempt for my body, contempt for other bodies. Those thoughts still pop up, even though I understand better the damage they can do.

+ + +

Sometimes I betrayed those thoughts in my writing.

Writing has been a way to motivate myself, maybe spread a little motivation to others who might enjoy it. I think this is, in principle, a worthy endeavor. I've always used writing to to see if my ideas make sense and to improve them, and the promise (threat) of a small audience raises the stakes enough to make it meaningful. I feel reward when a reader comments that something clicked, gave them an idea, helped.

But when you write, in part, as a tool to root out error…. a corollary is that frequently, the error spends some time noodling around on the page. And one might not catch them all. It's not inherently wrong to try to work out ideas in public that way. But there are limits.

First of all, I have to be clear about what I'm doing (sometimes, literally, making it up as I go along).

Second: when the topic is one that has been as historically fraught as exercise and diet and body image and fat loss, one about which many people carry a great deal of internalized harm… I need to be selective about setting down those first drafts of my thoughts.

Because I also carry internalized messages that have power, and maybe not just over me. Some of my thoughts are not great, especially some that in the intervening years I've learned to recognize as intrusive thoughts. It might help me to exorcise them by giving voice to their content, but will it help anyone else? If I'm going to straighten myself out by writing about those, best to write them longhand on one of the yellow pads I buy by the case, at least in first draft. And maybe just keep them to myself, or share with a therapist instead.

+ + +

It's hard for me to precisely sort my previous writing about this stuff into "definitely okay, maybe even good" and "definitely problematic." I've considered going back and editing, but the task is too overwhelming. I've considered deleting stuff, but I think there are kernels of insight there worth rescuing. For now it's still all there, waiting for me to decide what to do about it.

Meanwhile: I'm changing up my lifestyle once again. I'm committing myself to strengthen patterns of thinking that are much more compatible with good mental health and body care. I would very much like to clarify them by setting them out on the blog.

But: when I blogged about fitness and nutrition before, expressing what I was going through 10-12 years ago, I wanted to write conversationally and frankly but that really amounted to being careless: careless about language, careless about the words I used relative to the philosophy of the human person; careless about how pouring all my unfiltered thoughts out on the page might affect people who have a history of eating disorders, or of scrupulosity, or of difficulty caring for themselves. I don't want to make the same mistakes again.

Would it be better just to… not write about this sort of thing at all? I'm open to that possibility. I'm not sure I can find out unless I give it a try.

What if I could write about it without making those mistakes? What would it look like?

+ + +

Ground rules.

1. I will not conflate weight, fatness, or appearance with health.

It's not just that these, as indicators of health, are poor and incomplete—though they are.

It also means no more blithe writing about "desire for health" as a nobler-sounding euphemism for desires to look better, be less fat, or weigh less. Pretended concern for "health" has justified many rude and abusive people. Let me call things what they are.

A crucial reason to carefully acknowledge the difference: Fat people frequently report that health care providers become fixated on fatness as the primary indicator of their health, the sole probable cause of pain or other symptoms, and the first problem that must be "fixed" before they are allowed to access other levels of care. (See this recent commentary by Aubrey Gordon.)

2. I will acknowledge other biomarkers of general health that are better-supported by evidence.

Anyone can self-assess the time they spend physically active, the number of alcoholic drinks they have per week, the hours they sleep, the number of fruit/vegetable portions they are able to serve themselves each day. These behavior-based markers are much more often under an individual's direct control (although the range of available choice varies). Hydration can be assessed by checking if the urine is consistently a pale yellow color. Blood pressure, lipid panels, and blood glucose testing are accessible to those who can afford at least annual basic preventive care.

As for body-size-related markers of general health, my understanding is that neither body-fat percentage, nor weight, nor BMI work well at all as a predictor of eventual development of cardiovascular or metabolic disease. The one exception may be waist circumference. If I find myself casting about for a NUMBER, perhaps that one will work; otherwise, maybe I need to write something else.

(Two examples of papers with this finding; two examples don't substitute for a careful literature review, of course. Note that adjusting the results for BMI does appear to improve the correlation. This is possibly because it brings in a dependence of height; naturally short stature is itself an attribute that raises the risk of developing these diseases.)

3. I am not a fitness professional. I am not a health care provider. I am not a registered dietician.

I have my own experience. I have scientific training; it is not in this field, but I have good scientific literacy and am able to assess the general usefulness of papers and applicability of research. I know where to go for more information, and I know how to identify the difference between a broad scientific consensus and a matter with competing viable theories. I also know how to take a piece of popular science writing and pick it apart, if I want to, or use it for entertainment purposes, if I want to do that instead. All these mean that I can form an educated and reasonable opinion (you will not catch me scoffing about "Dr. Google," any more than I would scoff at public access to medical libraries), and I can write commentary about it if I like. These are not, however, substitutes for authority. I'm an educated amateur, not an expert in any of these areas, and I have an academic responsibility to remain clear about that to anyone who stumbles across my blog.

(This isn't a ground rule about which I really needed a reminder. I try hard to live by it anyway. But I thought it worth mentioning for completeness.)

4. No biomarker, and few health-related behaviors, imply a specific moral conclusion.

Yeah, I know myself (imperfectly). I might be able to tell you when I've made a poor choice, or developed a poor habit, or experienced a consequence, for lack of some virtue. I know where I have agency, and I have some ideas where my agency has been damaged by circumstances. I don't know that about others. I can't speak for everyone else.

Assumptions about real people are tricky at best, and at worst they are outright bad and harmful.

Moreover, the following ought to go without saying: there are no bad foods, there are no bad bodies, there is no such thing as cheating. There is room for rest, and room for feasting, and room for fun, and no one else gets to tell you how much; there is room for you.

5. Nevertheless, I'll stand by this: morality, theology, charity, the philosophy of the human person, the demands of justice, aren't off limits here.

Nothing that human beings do or decide is untouched by the disciplines and philosophy of my faith tradition, and there aren't many traditions that pretend otherwise for themselves. I hope to explore them in a way that doesn't violate the very principles I'm seeking to understand. I'm not certain that I can, but I hope to.

It is good to use appropriate self-discipline to strengthen virtue. It is good to consider how to use resources prudently. It is good to exercise detachment from outcomes. At the same time, discipline is personal, resources are personal, outcomes are definitely personal. So I need to take care: if I write about my discipline and my resources, I need to make clear that they are mine and no one else's.

6. I will be explicit about the limits of hypothetical situations and imaginary characters.

Ah, the hypothetical situation. Much maligned for good reason, sometimes useful for illustration, always a bit tricky in their execution.

I love hypotheticals, but I must be more careful with them. It is tempting to think that if I think up a hypothetical situation, decorate it with only those details that seem to me significant, and imagining human-like actors, I can treat it as my very own creature of pure reason. Since it is mine, I can manipulate as I please and judge with omniscience.

In one sense it's true, I can do that. But real human readers have a tendency to see in these hypothetical characters someone "like" themselves, or perhaps real people they know. And I am not allowed to manipulate or to judge the real person based on my fan-fic.

Even if I think up a hypothetical, and along comes a real person who embodies the imaginary one in every detail I created, I can't use my reason to reach deductive conclusions about the real person. Why not? After all, the hypothetical (in this hypothesis) is perfectly matched! Well, the real human may possess every detail of my hypothetical, but the hypothetical on which I exercised my reason could not possibly possess every detail of the human. Humans possess an infinite detail and and an infinite worth, far beyond the scope of any model problem. So watch it.

Once again. Watch out when you are tempted to make assumptions about real people.

7. If I write about specific activities, I'll make room for modifications for different bodies, variations that make training plans more enjoyable, and goals unrelated to weight reduction.

That short wish list appears in this commentary piece by Rebecca Scritchfield.

8. Athletic performance metrics are useful, far preferable to body-size metrics, but highly individual and unrelated to either value or virtue.

It's probably a step in the right direction to go from "my body's value comes from its appearance" to "my body's value comes from what it can do." But it's still wrong.

Training is experiment, and experiment requires observation and measurement. I can use performance metrics to evaluate whether my training is having the effect I desire. I don't have to be clinical about everything, either: I can celebrate when I meet the metric goals I've set, and I can express disappointment when I don't. It's crucial not to connect the results to my value or my "good"-ness. People do not, in fact, get what they deserve.

9. "Quality of life" is a universal goal, but an individual measure: how closely reality matches a person's hopes and expectations.

There are multiple ways of going about working for one's quality of life, too. Much fitness writing is aimed at improving quality of life through hard work; but I also want to honor the effort to maintain quality of life in situations of increasing difficulty. There is also the tough mirror process of re-adjusting those hopes and expectations to match an unlooked-for reality, maybe in the face of injury or illness, maybe other changes in circumstance, maybe after learning more about oneself.

10. The big picture of what I'm getting at: an authentically human understanding of self-care.

Maybe that sounds like an overly grandiose aim. Especially since, if history is any guide I'll probably be putting up posts like "here's what's in my gym bag these days!" and "I've discovered that it's a mistake for me to forget to eat breakfast before swimming a mile!" I mean, some of that stuff is really just minutiae. I might put it up because it's on my mind.

But all the little pieces add up to a bigger picture.

The ground rules are here as a kind of checklist for the construction of those little pieces, so they're all align-able with the sort of big picture I want to have. At the same time, there are questions that feel very open to me, so that I'm constructing that picture as I go along without really knowing what it will look like. What boundaries are essential? If vocation is about self-gift, what is the type and extent of self-investment that is appropriate for each vocation? How do we write sensitively about practices that are health-promoting for many but not for some? How about writing about practices that are accessible only to a few but might be interesting to many? How does a family distribute resources (time, effort, assets) among its members with different needs? Can self-discipline be taught or only discovered? What are the signs that health, wellness, even discipline has become an idol, or an obsession, and how can a person get their priorities back in order?

+ + +

Well, this post has been many days in the making, so don't be surprised if it takes me a while to get around to the actual writing. But it was a necessary step to unclog the pipes, so to speak. I hope to follow up on it soon.