This week my oldest son, now a homeschooled high school junior, needed an "official high school transcript" for the first time.

(He's applying for PSEO programs next year — that's "post-secondary enrollment options," i.e., earning college credit and high school credits simultaneously — and one local university that's rather selective about its PSEO applicants required it.)

I knew this was coming, and of course I am going to need it for college applications in the fall anyway, so I have been pulling together materials for a while.

+ + +

I feel much more excited and confident about guiding my offspring through the high school years than I ever did about dealing with elementary school or early middle school. Perhaps it mirrors my own feelings at those ages: I struggled a lot with fitting in, and with not being able to control my own environment, when I was younger, and don't have many happy memories, but in high school I began to find subjects to delight in (chiefly chemistry and physics, but also French and literature) and what's more significant, people who also liked that sort of thing. It was then that I began to see a light at the end of the tunnel, so to speak.

Now that I write that, it doesn't seem a particularly unusual story and so it can't possibly be the sole explanation for why I find a lot of elementary school stuff tiresome and boring compared to some of my colleagues who seem to have an endless, envious capacity for crafts and reading aloud and seeing the world as fresh and new all the time. Perhaps I am the tiresome one!

+ + +

The institution whose application we are mailing today, wisely in my opinion, does not wish to see grades issued by a student's parent, so my transcript has no grades.

To this I say: Excellent.

Not only is it a pain to calculate and assign grades to your own child, it's stupid. Why on earth should a university believe what I have to say about my own child in an application for admission to anything? Presumably the obvious conflict of interest would be enough to say "you know what? Just: no. We're going to go off the test scores and maybe an essay." And then there's the question of how meaningful grades can be when there are literally no other students in the class to compare this one to.

You would think that all the colleges would see the essential worthlessness of grades produced by a homeschooling parent and actively discourage the student from sending any grades issued by a parent. But I'm here to tell you that, at least as of last fall, several of the colleges which my oldest is thinking of applying for as a freshman not only encourage homeschooled students to submit a transcript with grades, but they require them.

I will issue those graded transcripts if I have to, but I really would like to include a disclaimer that says, "You know, I essentially made these grades up. On a rational basis, of course, me being who I am, but a truly rational basis would mean that you and I should both admit that I could give any grade I wanted to this student. And by the way, so could everybody else who chose to go the non-umbrella-school route."

+ + +

So: this time anyway, no grades. Don't even send 'em! says the university (good). But they do want to know what the student's coursework was like, and in particular how challenging it was. So: "Home School transcripts should include a narrative of the material a student has covered and a listing of courses they have taken, if appropriate."

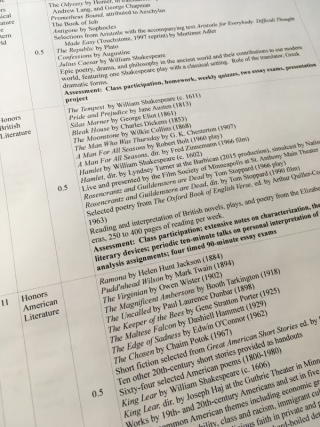

So I pulled out all my records for the various subjects that my oldest has worked on for ninth, tenth, and eleventh grade, and I made lists of the textbooks we used and the material we covered. I asked H., who has run pretty much all of my kids' English literature and composition, for a course summary, and she provided me a nicely detailed one. I wrote up a set of end-goals for each area of study (e.g., in Mathematics, one of my oldest's goals is "advance to differential and integral calculus by early in Grade 11 in order to apply them to the study of Physics I"). And then I sorted it all out first by topic and then grade level.

+ + +

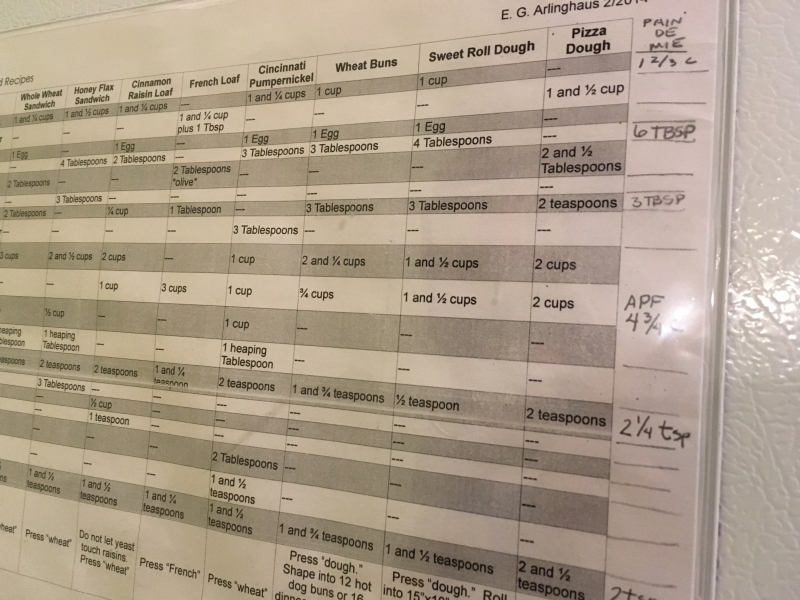

So, not everyone chooses to do it this way — lots of homeschoolers have a free-form, holistic, or interdisciplinary philosophy of education, where the boundaries of the different areas are soft or nonexistent, and that is fine — but I am naturally a put-it-all-into-boxes sort of person, and so from the very beginning I set up my son's high school years with discrete courses and credits in mind. There would be a chemistry class, and we'd do these chapters from this book. There would be a civics class, and we'd have three meetings a week for thirty-four weeks. There would be a Latin class, and we'll work through this syllabus published by an umbrella school. Physical education? Each session of the indoor climbing team is thirty hours of instruction, and at 120 hours = 1 credit (the Carnegie unit), that means 1/4 credit each session.

When you start off thinking this way, there is definitely a tendency to get boxed into rigid ideas about the boundaries of disciplines. On the other hand it is pretty straightforward to add up credits at transcript time.

Another reason I have thought this way from the beginning is because of my co-schooling arrangement. I set up physics and chemistry for a few high school students to learn in a group, facilitated by me. Their parents weren't watching me do it (at the time, for example, H. was busy at the moment, teaching language arts to 3 of my other children and 2 of hers). They trust me but they still need a record of what the students learned; after all, I'm not their "official" teacher; more like a tutor to which they've delegated some of the physics oversight. So from the very beginning I had a weekly schedule for the whole year, and I kept careful records of what we did and didn't cover. At the beginning of the year I write a course plan with my objectives; at the end of the year I write a new one where I write how I actually wound up making it all work. And I do give grades, which is not so hard to do objectively with the kind of coursework I facilitate. (Whether they are representative or not of what the student would be getting in an institutional school, I don't know. I hardly ever give anyone an A. I have a deep suspicion that it would depend on the school.)

+ + +

My son and I went to an informational session last week on campus, where you could ask questions of the full-time PSEO advisors and the program admission staff. I hung back to ask my question at the end while everyone was filing out — "What exactly are you looking for in a homeschooler's 'narrative transcript?'"

The staffer explained that the point was so that they could understand the scope of the material the student had covered in his classes, and in particular, whether he demonstrated the ability to do college-level work; it is very important to them that the PSEO students do not overextend themselves.

"So," I suggested, "you would want to see a list of the texts he read in his English classes, that sort of thing?"

"Oh my goodness, no, you would not need to go into that level of detail!" he chuckled.

I looked at him levelly for a moment. "Supposing I did go into that level of detail…" I said carefully, "would that be a problem? I mean, would you all hate me if I sent you, er, a rather detailed transcript?"

He assured me that this would not be a problem either, and I went away hoping that if the transcript was an outlier, that it would not at least be the sort of outlier that the office would laugh at. Because I wasn't about to delete all that stuff I'd written (although I did cut it down).

+ + +

One of the things that feels weird about writing out the transcript is that it feels like my son should be writing it. I rather don't like stories of helicopter parents (and I have enough friends who are college professors that I have heard such stories). I have a great distaste for filling out parts of applications for my student. He should do the application himself! You don't want your parent filling out an application for you, not for anything.

But: Transcripts are never made by students for themselves. They are made by institutions for students. They are sealed in smooth blank envelopes to be transmitted cleanly and with no signs of tampering from one institution to another.

I am not the student's educational institution. I am a mother, the original alma mater. This identity feels positively warm and sticky compared to the cool, blank, efficiency of the transcript. And so there is no way I can produce this document and be wholly comfortable with it. I know the institution is used to a column of numbers, and that from me the column of numbers is no good, so instead they get a document which I can't help but see as smudged all over with maternity. And that is something that I have never been comfortable with sending out into the world. I feel I want to run after the transcript with a corner of my skirt and dab it off, except that to do so would give away the truth.

But still, he can't do this part. I have to do this part, because I am the school. So I write the damned thing anyway.

+ + +

Deep breath. I open up the transcript file again and read my own deathless prose from the introduction to the Science section. I want it to be as much like a column of numbers as a narrative description can be:

The student chose to fulfill the biological sciences requirement with a non-laboratory course in evolutionary biology. Introductory college textbooks on evolutionary biology are supplemented with additional textbooks, videos, and assorted readings covering necessary fundamentals of biology and touching on the historical context and social impact of evolutionary theory.

Physical sciences are taught directly by the parent, who holds a PhD in chemical engineering, in a small group of high school students. Because texts are college-level and syllabi are modeled after APⓇ courses, we have designated these as honors courses.

I am second-guessing myself already (why did I mention the doctorate? does it make me sound like the sort of person who insists on being called Doctor all the time? does it make me sound insecure? will they look up my thesis? oh no) but at least I am sure have properly formatted the registered trademark symbol.

+ + +

Here's the thing. It's … not about me. There is a temptation to look over it and think that it is, at least a little bit, about me, or at least about me-and-this-kid's-wonderful-dad. It's not about me. It's about our son, this particular young man, this bright and earnest and funny young man, and about demonstrating that we all have good reason to expect he won't fall on his face when he takes his first college classes.

+ + +

In any case, it's done. They certainly will have an idea of the applicant's coursework. Probably several ideas. I'm glad I had a chance to do this, my first one, under relatively low stakes. I might be less detailed next time.

As I have five children, however, I must say that I am already wondering if high school transcripts, like baby-picture albums, get progressively less detailed as one moves through the younger children in the family. You know the trope: your first child has a beautifully kept scrapbook, your third has a stack of photos in a manila envelope, and — did you even take any pictures of that fifth child?

I would bet there was a correlation.

(Except that I never managed to make any baby albums.)