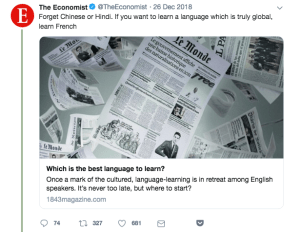

A couple of weeks ago The Economist tweeted out a link to an 2012 article from their lifestyle arm, 1843 Magazine, entitled "Which is the Best Language to Learn?"

(image not clickable)

The caption/link writers were a bit too vague. I think this for two reasons:

First, they mention too subtly that the article is aimed at native speakers of English. Granted, the problem is not entirely on their end, but we can all learn to be more clear from the flood of Twitter comments complaining that English was not identified as the best language .

Second, more pointedly, the tweet suggests that clicking on the link will lead you to an article decidedly in favor of English speakers learning French.

It's not! It's better than that, and I only wish the editors had made the feature longer. It's actually six separate pieces, written by six different people. It's almost like a panel discussion with six speakers, each making an argument for learning their own favorite languages:

- French

- Spanish,

- standard Chinese, aka Mandarin

- Arabic

- Brazilian Portuguese

- Latin.

The feature has a major structural flaw, which probably contributed to the bad captioning. The piece ought to have a distinct introduction, followed by arguments for each of the six languages. Unfortunately, the introduction-writer and the French-learning-cheerleader are the same writer, as if one of the panelists was also the moderator. He didn't take care to separate these two rhetorical tasks (not only that, but he feels the need to defend French from Chinese in particular, something that comes across as a sort of pre-buttal of the Mandarin fan whose bit appears later).

And of course, I'd have loved for the feature to have been even longer and included arguments promoting the learning of even more languages. Even more importantly, I'd have loved to see more attributes of different languages being considered.

Still, they covered most of the key points to consider, and promoted language learning in general. All too often, languages are suggested to English speakers merely on the basis of "usefulness," which in practice is rhetorically limited to considering the likelihood that one expects to have economic transactions in the language.

But there are lots of different reasons to learn languages, and the six "panelists" touch on many of them:

- acquiring meta-language that allows you to understand and use all languages better, including your own

- broadening your cultural understanding in general

- deepening your cultural understanding of whatever particular culture you are most interested in

- grasping, a bit, another way to think about various concepts, say through interesting idioms

- career preparation for conducting international business

- career preparation for conducting diplomacy

- reading literature

- enjoying the challenge

And what's great about this article is that it acknowledges that different languages fulfill these needs to varying degrees and in different ways.

And individual learners' tastes and ambitions matter more than anything. Even the pro-French, Chinese-isn't-all-that-it's-cracked-up-to-be introduction writer says: "By all means, if China is your main interest, for business or pleasure, learn Chinese. It is fascinating, and learnable."

Beyond a particular interest, though, what are the arguments for each of the six featured languages?

- Robert Lane Greene prefers French, calling it the most global language, with native speakers in every region; it's relatively easy for English speakers to learn, with grammar not very different from ours, and a great deal of vocabulary overlap.

- Daniel Franklin promotes Spanish. It has an enormous number of native speakers, is a regional champion, is heavily used on the Internet and as an international language, and has great literature and film. Like French, it is relatively easy for English speakers to learn (and, I'd add, is far easier to pronounce and to spell). It's also a bridge to Portuguese and Italian.

- Standard Chinese, says Simon Long, has the most native speakers and its economic importance is growing very fast.

- Josie Delap makes an enthusiastic aesthetic argument for Arabic: difficult for English speakers at first, particularly because of the new script, but extremely rewarding and beautiful to learn (as well as an impressive feat).

- Helen Joyce argues for Brazilian Portuguese on the grounds that it's not very difficult, invites you to visit and work in an interesting, beautiful, and half-continent-sized nation (plus a few other places), and will help you with your Spanish/French/Italian while letting you stand out from people who've chosen those more common second languages.

- Tim de Lisle begins by humorously stressing the lack of direct usefulness of Latin, but argues that it strengthens your linguistic "core," improves your understanding of grammar and syntax, requires rigor, and (perhaps ironically) claims it makes it harder to bullshit. Its vocabulary is everywhere and its surviving literature is timeless. He seems to argue that it is a great pleasure for a particular kind of nerd.

So, across these few paragraphs, we have languages defended because they are easy and also because they are difficult. Because your language has many second-language speakers, and because it has few. Arguments based on economic importance, and arguments that concede nearly no economic importance at all.

It really depends on what your goal is.

+ + +

There are a few more attributes for choosing a second language that aren't mentioned in here, which I would add. Mine are:

- Ease of accessing resources to learn a specific language in your town

- Number of native speakers living near you

- Closeness to English on the language family tree (which brings a kind of "easiness" that is distinct from the sort Latinate languages have).

I never really thought about these three much until two things happened in our family.

First, something just for me: I decided that for no reason other than personal interest, I wanted to learn a non-Indo-European language. I wanted to explore a grammar that behaved sufficiently differently from the other languages I knew to give me a broader understanding of human beings' relationship to language, and see how different words worked together to create idioms.

In Minnesota overall, the non-Indo-European language that's spoken most widely is Hmong; but in my city, Minneapolis, public school students are much more likely to speak Somali at home than Hmong. (In fact, they are nearly as likely to speak Somali as Spanish.) That plus the convenience of not having to learn a new alphabet made it an obvious choice. Not only do I have the chance to encounter native speakers regularly, but there are materials available which have been produced for Somali speakers: signage, library books, newspapers, a radio station. So even though my progress is fairly slow, as I work in my spare time through an imperfect text and meet a small study group monthly, I constantly get little affirmations from overheard snippets of conversation, from "thank yous" and "good mornings," and from being able to pick out words from signs and newsprint. I don't know if I'll ever be able to have a real conversation, but I am enjoying the journey.

Second, for one of my offspring, who begged to be allowed to quit Latin. We all learn Latin at home because (being dead, and pronunciation and conversation unimportant) it's really well suited to the homeschool. Most of the kids enjoy it, but one of mine… didn't. He didn't have a particular desire to converse in a modern language either; he was struggling, and he needed something easier, because some language in high school is required for college. "Anything but Latin!" he told me.

Well, if "anything but Latin" will do, then I was free to find something that would be relatively easy to arrange.

I speak French passably, read it fluently, and could probably have scraped together the time to teach it. But I suspected that "Anything but Latin" also served, for him, as a tactful way to express "Anything but learning more language from you, Mom, who is a complete language nerd and can't deal with the fact that I find this really difficult."

So I looked outward, and discovered relatively inexpensive Saturday-morning classes in Swedish, of all things, within walking distance of our house.

Swedish doesn't hit many of the reasons from the article for why an English speaker would want to learn it. It doesn't have global importance; its native-speaking population is small and almost entirely living in Sweden and Finland; fewer than 60,000 people living in the U. S. speak it at home (although, granted, a lot of them are probably living in Minnesota). Finally, Swedes themselves overwhelmingly learn English and have even been called the "best in the world" at speaking it.

What it does have going for it — besides the convenience of having classes available, and the fact that it is possible to supplement with commonly available commercial and online learning programs — is ease. Although there's definitely grammar and vocabulary to learn, Swedish is possibly the easiest language for an English speaker to acquire. And that is exactly what my son needed. He has realized that learning a foreign language is something he can do. And, surprising to both of us, he actually enjoys it.

It's also slightly quirky, an unusual choice for an American kid with no Swedish heritage, and I think he enjoys that. He had a fun time seeking out and greeting a small collection of very surprised Swedes at World Youth Day in Panamá. We have a photo of him posing with them, grinning and holding the Swedish flag.

I'm just saying, sometimes making it as easy as possible is the right thing to do. There is no shame in that.

+ + +

So, to sum up, what I've said before: Really considering what you'd like to get out of a language, honestly — whether it's "I want to read cool literature" or whether it's "I just need the minimum possible so that I can get into college" — is key.