I last posted that, as I prepare to teach civics to a few homeschooled kids next year, I find myself enmeshed in a cynicism that makes it hard to get excited about passing it on. My old motivations feel too o ptimistic, and until things turn up, I fear I need a different set.

So I am going to try to take a more pragmatic approach to the question: why are we learning this anyway? And I will take that approach by starting from a rather cynical-sounding assertion, inspired by Ilya Somin’s work of a few years ago, the book Democracy and Political Ignorance.

(I have not spent enough time with Somin’s arguments to decide if I am fully convinced by them, but they are interesting and worthy of consideration. He outlined them in a series of posts,beginning here, on the Balkinization blog some years ago; and in an article for Cato Unbound.)

Somin argues that, given the complexity of our political system, it takes significant time and effort to acquire sufficient political knowledge to make wise choices about the various options in any given election. People know this. They also know that one vote does very little. That is why they reasonably do not choose to be informed.

In short, here are the assertions:

Most political ignorance is rationally chosen.

and

An individual voter has virtually no chance of influencing the outcome of an election.

I want to begin by assuming arguendo that these assertions are true, and yet, to articulate a motivation for expending costly effort to learn the content of the high school civics course that I plan to facilitate.

In other words, either

the information content of the high school civics course is more valuable than most political information;

or else

there are other uses for political information, besides influencing an election with a vote, which make its acquisition more valuable in circumstances where those uses can be exercised.

So let’s take a look at both.

+ + +

I. The political information content of the high school civics course is extra valuable.

A. It contains locally tailored information.

First let’s concede that the insignificance of one vote is relative. As elections become smaller and more local, the power of an individual vote increases. Your vote is worth many times more in smaller states than in larger states, in municipal and district elections than in state elections, in primaries than in the general election, on obscure and boring referenda than on interesting and controversial referenda. So, although the chance of swaying any of these may be quite low, it might be rational for a purely utilitarian voter to expend the effort to learn about small and local elections but not about large and statewide ones. Therefore, one of our principles might be: Local political information is worth more.

And indeed, my high school civics course includes local political information. Since we all live in the same general area, and the class is small, I can tailor my course to the individual students’ districts. Each of the teens will learn who represents them in the state house and in Congress. They will develop lists of the most pressing issues in their own community; they will find out when the next municipal elections will be held; they will learn about the local flavor of the national political parties; and they will project which issues will likely be on the table in the first local election of their eligibility to vote (2020 and 2021).

But the local information is only a small fraction of the course; and again, even in small local elections, the individual vote has low absolute value. It’s just that it has more value than in large elections. So I will have to look for another source.

B. Rather than information on specific issues, it contains structural information that is useful across many issues and from year to year.

We will spend a little bit of time talking about political issues and current events, because there will be times when particular examples will illustrate a greater point.

But most of a basic civics course is about the structure of the government and how power and responsibility is distributed (and how it might possibly be redistributed through ordinary channels). This makes the information more valuable because it applies all the time.

So, for example, rather than spending a great deal of time on background information that would help students decide how they should vote on a particular issue, in this course students will learn how to determine who can, and cannot, take action on what sorts of issues.

- Which officials are responsible for each issue?

- When are social conditions directly impacted by policies and when are they largely out of the immediate control of politicians?

- Which branch of government has power over the aspect that you would like to improve?

- Which level of government–local, state, federal–is in charge of this particular problem?

- Whom do you approach when you have a complaint? Do you contact your congressional representative, your city council member, the mayor, the chief of police, the school board, a judge? Or someone not in the government at all: a party official, the local newspaper, your neighbor?

- What's the process for changing the law and the Constitution?

There are also some conceptual basics, some of which are matters of fact and some of which are matters of philosophy:

- How do checks and balances work? Is your "obstruction" my "safeguard?"

- A good deal of history: how did we wind up with a population-based House and a not-population-based Senate? why are there nine justices on the Supreme Court and not five or twenty-one? why do we have exactly two major parties?

- Where do rights come from? Can a right exist if a government has not agreed to protect it?

- When is it important to make a law uniform across the country, and when does it make more sense to have the law be different in different places?

- What is the value of compromise?

- What is the value of tolerance?

- What is the value of a freedom to say and do things that are wrong?

- Is it possible and good to live peacefully with people who are very different from us? Or should we always be struggling for dominance so that "our" idea of how to live a right life will come out on top?

- What happened, at each step, in the lives of people who had the least political power?

The point of all this is to acquire the habit of thinking a step more deeply and being aware of the tensions that are inherent in the structure of U. S. government. There is a lot of balancing two goods that cannot perfectly co-exist, or trying to eliminate one evil without also eliminating something good with which it is entangled. There is a great deal of historical justification of why certain classes of people ought not to be able to access the benefits and protections and rights that are secured by "regular Americans," the definition of which is constantly shifting.

Sometimes the habit of thinking historically helps: if you know a little about how the sausage was made in the past, then you know to be skeptical about proposed future encased meat products. The structure and processes of American government were not handed down to us on high, but were put together by human beings–exceptional human beings, no doubt, or such a structure might never have been formed; but unrepresentative in their exceptionalness, and deeply flawed; everyone is flawed, but these folks (being exceptional) were flawed in some systematic and exceptional ways. They left us a way to change their work, and that is a power for both good and ill.

There are no perfect analogies, and every historical situation is different; still, we can see through some of the rhetoric of the past with hindsight, and developing that habit, maybe we can see through some of the rhetoric of the present.

I don't have to get too embroiled (or angry) laying out the details of What's Going On right now. Mind you, it's extremely important to avoid falling into the error that all the bad things happened in the past and now we've gotten over them, so it's not a matter of "back then bad things happened"; it's more a matter of pointing out the continuity of themes of history. The First Amendment and the Fourth Amendment, the Equal Protection Clause, the opening and shutting of the Prohibition era, the meaning of citizenship, the role of commercial operations in public life, the role of ideas about powers that are higher than government itself, asymmetrical power and asymmetrical freedoms and asymmetrical protections: all these are still in play.

II. There are other uses for political information besides the (relatively worthless) casting of a single informed vote.

In Democracy and Political Ignorance, Ilya Somin asserts

Only those who value political knowledge for reasons other than voting have an incentive to learn significant amounts of it. Acquiring extensive political knowledge for the purpose of becoming a more informed voter is, in most situations, simply irrational. This point applies even in cases when political information is available for free… As long as learning the information and analyzing its significance requires time and effort, the process is still costly for citizens.

This is true even for highly altruistic and civic-minded citizens, he argues:

the rational altruist would … seek to serve others in ways where a marginal individual contribution has a real chance of making a difference to their welfare, such as donating time or money to charitable organizations. By spending time and effort on becoming an educated voter, the altruist might actually diminish others' welfare by depriving them of the services he might have conferred on them through alternative uses of the same resources.

So if we accept all this, and we seek an incentive to learn significant amounts of political information, we must work out whether we have some reason other than voting to motivate us. I think we do have these reasons. Let's take a look.

A. (Trivial use): A course of some kind in U. S. Government is a state graduation requirement.

I include this only for completion of the argument, but it is worth noting because it is important to me. While homeschooled students do not strictly have to meet the state graduation requirements, it is one of the goals I set for my home school. The diploma I issued personally to my first high school graduate stated that he had fulfilled all the same requirements that institutionally-schooled students must, and I meant it. I intend the same for my other offspring.

B. Contributing, in a very small way, to the public good of the "informed electorate."

Somin mentions this. An informed electorate is a public good. We all consume its benefits. If the teens expend time and money to become informed, if I expend time and money to teach them, then they and I are contributing to the production of this public good. The value is offset perhaps by the opportunity cost mentioned above: we might have expended the same time and money to serve the public in a direct way that is much more valuable. But these resources would only ever have been used on some homeschool course, after all, and likely another social studies course. I don't think it's crazy to think that working hard on a civics course might be the most beneficial use that we were likely to make of this aliquot of resources.

C. Preparing these teens in case one becomes an influencer.

There are some individuals who can and do use political information to influence society far more than by a single vote:

- journalists

- widely-read opinion writers

- policy makers

- lawyers and judges

- politicians and high-level administrators

- teachers at the secondary and university levels

- wealthy-enough donors to campaigns and to nonprofits

I don't know what these kids are going to do with their lives, but any of them could wind up in a position to have a nontrivial effect on communities through influencing elections and their aftermath. If they go in a direction that makes that possible, then the public will be better off if they have been well prepared and are informed. We don't know which young persons will become influencers; but we want all our influencers to be well informed; one way to make that more likely is to give everybody a good, thorough grounding in the basics.

D. If the subject sparks particular interest, it can be its own reward.

It can be difficult to escape political information; there's a bit of consolation for those of us who are self-described "political junkies," who like discussing politics with like-minded or differently-minded people of good will, and who are intellectually stimulated by keeping up on legal and political news (and perhaps engaging in activism here and there: citizen journalism, contacting officials, going to town meetings, showing up at demonstrations). Someone who enjoys political knowledge for its own sake, and for the sake of positive interactions with other people, will reap the rewards of an interesting and accurate treatment in the teen years.

Furthermore, if I am careful about the attitude that I bring to class and foster among the teens, I can set a good example for how to talk and argue about politics with charity, fairness, inclusivity, and truth-seeking. That is a worthy goal.

E. In order to truthfully and convincingly persuade others.

Persuading other people can reach farther than your own ballot, and can even reach into places where you cannot vote, such as in local elections in other states. It's very easy these days to put your thoughts out there and inflict them on the unsuspecting populace. Much better for those thoughts to be informed and not ignorant.

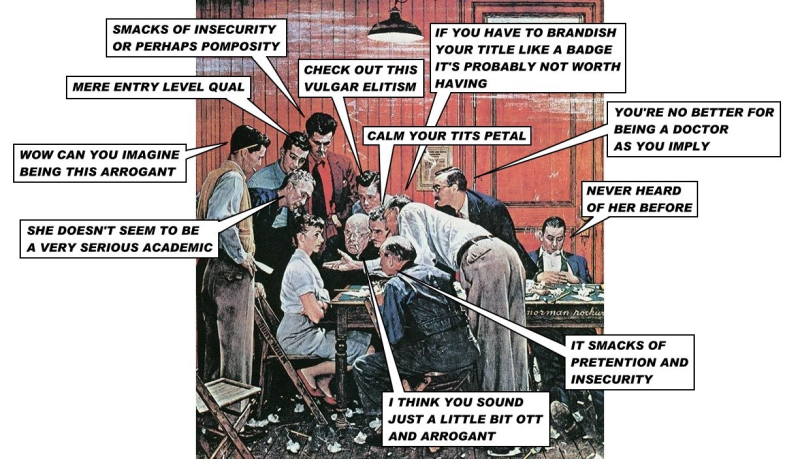

As a side note, it may be necessary for these young people to persuade others — not so much of political information — but of their own worthiness as an employee, a student, a writer, a thinker, a colleague. It would be a worthy goal to contribute to their intellectual development and knowledge acquisition as it applies to political information.

In other words, "so they don't look foolish."

F. So you can decide where to send your money or spend your time.

Political contributions, like persuasion, can reach outside your own district. We can support candidates anywhere in the country where we think the dollars will do the most good. But to decide where the money should go requires rather a lot of political information.

Knowledge of the structure of the nation, state, and city also helps you decide where to send charitable contributions and perhaps how to spend your volunteer time. Often charitable donations are a way to respond to the aftermath of bad law and bad policy: we can mitigate the effects of harmful legislation by directly helping the people who have been harmed by it. And we can also support nonprofit organizations which are committed to changing law and policy.

For example, we can respond to cuts in services for the poor by stepping up our individual almsgiving and support of civic groups that work to help them.

We can support organizations that provide lawyers to vulnerable people, or organizations that argue cases before the Supreme Court on behalf of individuals, businesses, and nonprofits, or "think tanks" that work to shape policy. But to envision these uses of our money requires considerable political information.

G. So you can "vote with your feet."

This is one of the points that Somin stresses the most, since it supports his overall thesis that decentralized federalism is the best system to promote citizen welfare and government accountability: "foot voting" has a direct and immediate impact. I have found it to be a fruitful point for motivating my teaching.

[O]ne of the main causes of political ignorance is the fact that it is "rational." Because even an extremely well-informed voter has virtually no chance of actually influencing electoral outcomes, he or she has little incentive to become informed…if the only purpose… is to cast a "correct" vote. By contrast, people "voting with their feet" by choosing the state or locality in which to live are in a wholly different situation from the ballot box voter. If a foot voter can acquire information about superior economic conditions, public policies, or other advantages in another jurisdiction, he or she can move there and take advantage of them even if all other citizens do nothing. This creates a much stronger incentive for foot voters to acquire relevant information about conditions in different jurisdictions than for ballot box voters to acquire information about public policy.

…It is an option that can be made available to most, if not all, of the population, and individuals' choices are causally effective in a way that ballot box votes are not. Moving costs and other constraints limit the extent to which participation in foot voting is ompletely equal. But… these constraints are not nearly as severe as conventionally thought. And, obviously, individual influence over government policy in ballot box voting systems is also far from fully equal.

Political information can be applied in the students' individual lives to answer many questions which will directly impact their quality of life and their interactions with government:

- Where will you live?

- Where will you buy property?

- Where will you go to school and how will you pay for it?

- Where will you raise children and how will you educate them?

- Where will you do business?

- Where will you select health care?

- What industry will you engage in?

- In what communities will you perform services?

- Which jurisdictions will receive your sales, property, and income taxes?

The more they can foresee interacting with government at the local, state, and federal level, the more important it will be for them to understand the ramifications of choosing the jurisdiction to live in.

I could add that the altruistic foot voter can also employ political information in order to decide — not so much where the economic and political conditions will help them prosper the most — but where they can do the most good for others. Particularly for people who are considering going into a career of serving others — health care, teaching, law, clergy — acquiring political information may pay dividends not just for themselves but for society at large.

+ + +

I feel like I need to write down a list of these "reasons to do a good job with this" and paste it on the inside cover of my teacher's edition. I think if I can keep all these at top of mind, I might be able to keep the cynicism at bay. And maybe it will give me some material for my first, introductory class: the one where I explain to them all why they are here, and why they should listen to me.