Once I was seated at a dinner next to an elementary school music teacher. It was impossible to avoid the topic of homeschooling, and the conversation turned to how I spend my typical day. At the time one of my children was in first grade, and I commented that I was in a stage where I needed to budget quite a lot of one-on-one time with that child, because he was learning to read. "I've found that reading instruction is intensive," I said, "it takes a lot of care and attention."

She nodded sagely. "Of course," she replied, "that's because you haven't had any training."

I believe I changed the subject soon thereafter, in order to avoid ruining everyone's dinner.

+ + +

In 2009, more than a quarter of high school graduates performed below the basic level in reading on the NAEP. Is it because their teachers didn't have any training?

I don't think so. Reading instruction takes a lot of care and attention even for classroom teachers who have had specialized training in reading instruction (incidentally — many don't). A few children are able to work it out on their own, of course, and the kind of instruction they are provided isn't going to matter much. At the other end of the spectrum, there are children for whom the necessary care and attention simply isn't made available — either they need a great deal, or their environment can't meet ordinary needs — and those children never do achieve basic literacy.

What about the broad middle? Pretty much everyone agrees that parents — even the ones who haven't had any "training" — should be deeply involved in their own child's reading instruction. That parents should spend time reading to children and helping children practice reading and writing at home. Check out this list of literacy activities recommended by the U. S. Department of Education. Care and attention, and time. Here's a paper strongly implying that the effort made by (untrained) parents is the most important factor in literacy development. And that's for kids who expect to attend "away school."

If we've taken on the task of teaching our own kids to read, we're basically looking at doing the same things that parents are always expected to do with their children, only more of it, and perhaps — if it suits our personalities — more systematically.

+ + +

I am nothing if not systematic, but I can also throw things together quickly if I have the motivation.

A decade ago, three critical factors were converging:

- I had just finished graduate school (engineering, not education or linguistics or anything like that) and still possessed the stamina to analyze the hell out of things in enormous spreadsheets.

- One of my closest homeschooling friends, frustrated by pedagogical difficulties related to her children's special needs, had thrown herself into the literature on reading instruction in order to develop her own reading program. She was regaling us all twice weekly with everything she learned. Her husband (whom I'd gone to school with) had written a nifty computer program for her, which searched dictionary databases to generate lists of words that possessed certain spelling combinations. He gave me a copy of the program to play with.

- My first child was learning to read.

Although my friend's program was far more involved, comprehensive, adaptable, and attractive, I managed to take some of her basic concepts and set up a "quick and dirty" method that I enjoyed using with my own kids. Hers was the idea around which I organized my own approach:

Instead of teaching dozens of contradictory phonics "rules" , I would just directly teach — one at a time — every phoneme-spelling combination that appears frequently enough in English.

So, for example, I might start out by teaching that "m" spells the sound /m/, but later I'd teach that "mm" also spells the sound /m/. Still later, I'd layer on top of that a lesson that "me" and "mb" sometimes spell the sound /m/ too, in words like "come" and "dumb."

In my system there would be no silent letters. I would not say about words like "sign" or "gnome" that "the 'g' is silent." Instead I would (eventually) teach that "gn" is one of the ways to spell the sound /n/.

At every stage, I would give the child practice words that incorporated only sound-spelling combinations they already knew. So, I'd never ask a child to read the word "sign" when the only /n/-spellings they knew were "n" and "nn."

Obviously, one skill that would need to be developed: trying out the different possible sounds that a given spelling might represent. Faced with "come," the child would simply have to get used to trying different possible pronunciations. "Comb? Comm? Comm-ie? Come?"

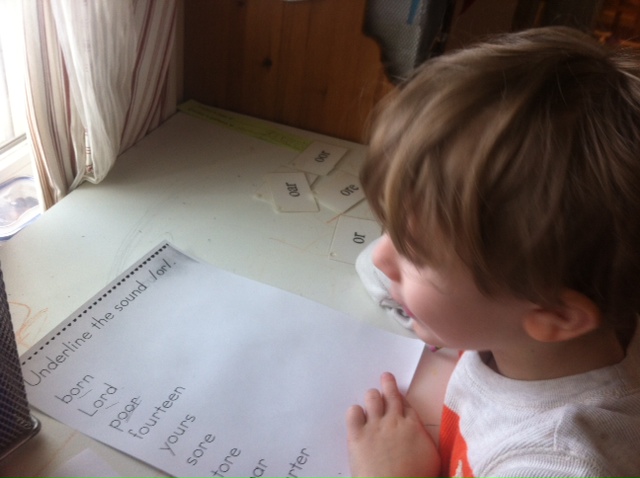

Eventually, the clues would come from context. But at first the clues would come from me, the teacher, sitting by the child's side: "It could be 'comb,' but that's spelled another way; try another sound that you know for the letter 'o.'" That's because I planned not to emphasize reading books or even sentences until the child could read individual words with confidence. It might be a little boring, but I was determined to get the fundamentals of word-decoding mastered before attacking lines and blocks of text.

+ + +

I didn't have a lot of theory to back me up. Still don't. And of course, I don't pretend that this system will work really well for every child. But I did find it to be "a thing that worked" for my own children.

Does it sound daunting? It is a bit daunting, but maybe not as bad as you think. Before my friend did her analysis and reported the results to me over tea, I believed that English was completely un-analyzable. I mean, we don't speak Finnish; aren't there effectively an infinite number of English sound-spelling combinations?

But my friend showed me that the total number is countable — somewhere between 200 and 300 in a really comprehensive list. If you exclude the ones that only appear in obscure words or in just a couple of words, the list becomes manageably short. In the end I settled on 41 phonemes (plus the lowly schwa, which is kind of a special case). On average, I taught 4-5 spellings of each phoneme. I think the total number of combinations was 175.

Yes, it takes a while. But it isn't impossible. And it seemed to work for us. In fact, I never have gotten through all 175 spellings, because the three kids I've taught so far have all taken off reading, partway through the list, and stopped needing help.

+ + +

In this series of posts, I'll walk you through my whole homemade program:

- How I set up my materials. (Not much more than writing tools and a really big pack of flashcards.)

- The first phase: one letter equals one sound.

- The second phase: Remaining sounds are introduced which are each spelled by one digraph.

- Interlude: A few "overlaps" are introduced, namely long vowels and s-that-sounds-like-z. Practice having to test out different possible sounds for the same letter.

- The third phase: Revisiting each phoneme with all its common spellings. (About sixteen weeks' minimum.

- A few ideas for building fluency as you go.

Again, this isn't something that I am exactly recommending. I never did any research to measure its effectiveness relative to commercially available reading instruction programs.

And, you know, I don't have any training.

But hey, the price is right. I hope you enjoy reading along.