by Mark

Don't get me wrong: for a small fraction of students, college is a great deal. Engineering majors are still earning plump salaries, and many of the business and computer science majors were greeted with good job offers at graduation. For most of the rest of the university community, the news is not so cheerful. Students have paid large sums of money to universities and received very little in return.

The truth is that the kinds of people who are capable of graduating from college would have done just fine if they had never gone to college.

For those not in top paying fields, borrowing money for college will, on average, make them poorer.

How do we know this?

Back in the 1990s, Ashenfelter and Zimmerman (1997) and Altonji and Dunn (1996) studied pairs of siblings to see how going to college affected earnings. (Their research is summarized in this 1999 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research.) They took pairs of brothers and pairs of sisters and compared their earnings, looking at how education level affected their earnings.

The findings are clear: most of the supposed earnings boost that is attributed to college is explained by family income. It stems from the fact that college students come from wealthier households compared to people who don't attend college.

(Simply put, the children of the wealthy will earn more money than the children of the poor regardless of whether they go to college or not.)

The real earnings boost of going to a four-year college is only 20%.

Going to college is a badge of wealth, not a significant creator of wealth.

+ + +

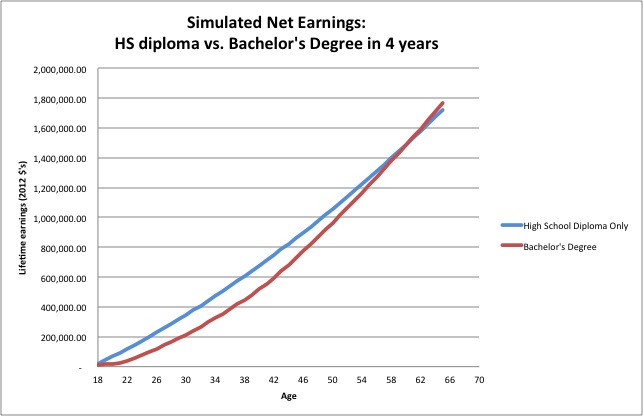

Once you factor in inflation; borrowing costs; and the loss of four years' wages, a typical graduate of a state university (in my example, the University of Minnesota) will not pass his or her high-school-educated sibling in net lifetime earnings until he has reached age 57.

Borrowing for a private school means you will not catch up until age 67 –or older.

+ + +

It gets worse.

The above assumes you actually finish the degree you start in four years.

But only 55% of U. S. students who start a degree program graduate within SIX years.

Once the real graduation rates are factored in, the financial benefits of college disappear.

The financial gains of the high-earning engineers, computer scientists, and business majors are wiped out by low-paying degrees and by those who start college, but never finish.

We should stop talking about "going to college" and instead talk about training for specific careers.

The return on investment (ROI) of a welding program might be less than that of a petroleum-engineering degree, but it beats a criminal-justice degree hands-down. If your son or daughter becomes a plumber, they can expect a wage as high as that of their friends who get an architecture degree.

Assumptions:

- The plots above show the simulated net earnings of two siblings: one who gets just a high-school diploma, and another who borrows money to pay for a four-year degree.

- The net earnings include a deduction of $5,000 in job-training costs from the income of the sibling who does not attend college.

- The totals are adjusted to include 3% inflation.

- The student's loan is taken out for 20 years at 7% interest.

- College tuition costs are assumed equal to current tuition at the University of Minnesota.

- The fraction of the loan that covers room and board is counted as income in the years that it is received.

- The loan payments are deducted from gross earnings to generate the net earnings.

+ + +

(This post is part of the series on postsecondary education.)