In March I suggested to Mark that we get a hotel reservation for August 20, 2017, in the path of totality somewhere, because I had heard that hotels were filling up. Within a couple of days he had gone online, searched, easily found a couple of rooms in a motel northeast of Kansas City for $80 each, and reserved them without fanfare. I think he may even have laughed at me a little for worrying that there would be nearly no rooms left, although he did warn me that they were not nonsmoking rooms. When we checked into that motel Sunday night, the clerk informed Mark that those rooms had only come available as a result of a computer glitch that incidentally left them underpriced for a two-day window, during which Mark had happened to log on. That had been the start of our luck.

+ + +

I was worried about disappointing everyone, about dragging the family down to Missouri only to see a cloudy sky; about thirteen hours of driving round-trip for a two-minute experience. I was also worried about being trapped in a gigantic national traffic jam. I was following people on Twitter who had made three, four, six lodging reservations spaced along hundreds of miles of the eclipse path. I knew people who would be in Tennessee, South Carolina, Wyoming. Two weeks out I started watching the projected "sky cover" forecasts. The center of the country did not look good. But that was where our reservation was, so we would go there anyway and hope for the best.

"Maybe," Mark suggested, "we can get up in the morning, check the forecast, and drive to get away from the clouds." I fretted, and I packed the car with 36 hours' worth of food and water.

+ + +

When I was a very small child I owned a paperback picture book called "Something is Eating the Sun." I think I remember choosing it at Books & Co. in my hometown. It was a riff on Chicken Little, a series of barnyard animals becoming increasingly worried about the bites being taken out of the sun's disk, page by page. The last page warned readers against following the animals' example and looking directly at the sun during an eclipse.

When I was a bigger child (almost certainly on July 6, 1982, when I was seven) there was a total lunar eclipse visible from my street. I remember being allowed to stand outside barefoot in the street after my bedtime. I don't remember what it looked like, but I vaguely remember being disappointed that it did not look like something was eating it.

I got older, and I learned about the solar system and the law of gravitation, Kepler's laws, the mathematics of ellipses, a bit of astronomy. I learned about how the Royal Society made observations during the eclipse of May 29, 1919 that tested the theory of general relativity. Total solar eclipses were a thing in the planetary domain that I had never seen but that I understood, the way I understood that the moon made the tides. I had studied ebb and flow, neap tide and spring tide, the lag behind the moon and the slowing of the earth's rotation. I had eventually been to the seashore and seen the water rise and fall, the moon's work between my feet and flowing cold around my ankles. Someday, I might see a total eclipse too.

I was a sophomore at Ohio State when I saw a partial phase of the annular eclipse of May 10, 1994. The square courtyard between McPherson Lab and Smith Lab was full of people trying to look at the sun through Pop-tart wrappers and CDs. I had no light filter and knew better than to look at the sun, but I could feel the temperature drop and see the strangeness of the light. I stopped to sit down next to some shrubbery; its shadow was spangled with perfectly identical crescents of light, an unexpected phenomenon that delighted me, none the less because I recognized the pinhole effect immediately even though I did not know to look for it until that moment. No one around me had noticed the shrubbery shadow yet, and it felt for a moment like a private secret between me and the universe.

That got me a little more interested. And when I encountered Annie Dillard's essay "Total Eclipse," much later, I began to think seriously: If I get a chance to experience an eclipse, I shouldn't miss it.

+ + +

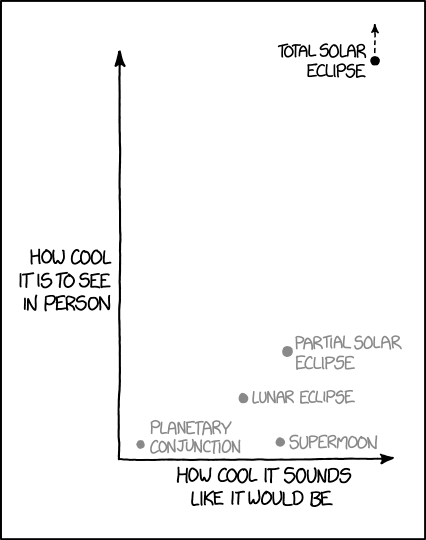

All this is to say that I knew what would happen. I knew, too, that other people knew even better than me. I know in the bottom of my being that the planets and the moons move in their elliptical orbits so simply and in accord with laws that are themselves so simple, that the locations and times of all the eclipses for hundreds of years in the future have already been mapped; so simple that indeed people have been predicting them for hundreds of years, before computers, before calculators, before pencils. Eclipses are a tame thing, a trivia question, a child's picture book, a just-so story. They may be rare, but they are a caged specimen. A famous gem of the natural world. I knew everything about them. I was even well informed, thanks to Annie Dillard, that they were an emotionally moving experience that was worth driving a few hours to see. I get it, I get it; we'll go. I knew it would be cool.

Or so I thought.

+ + +

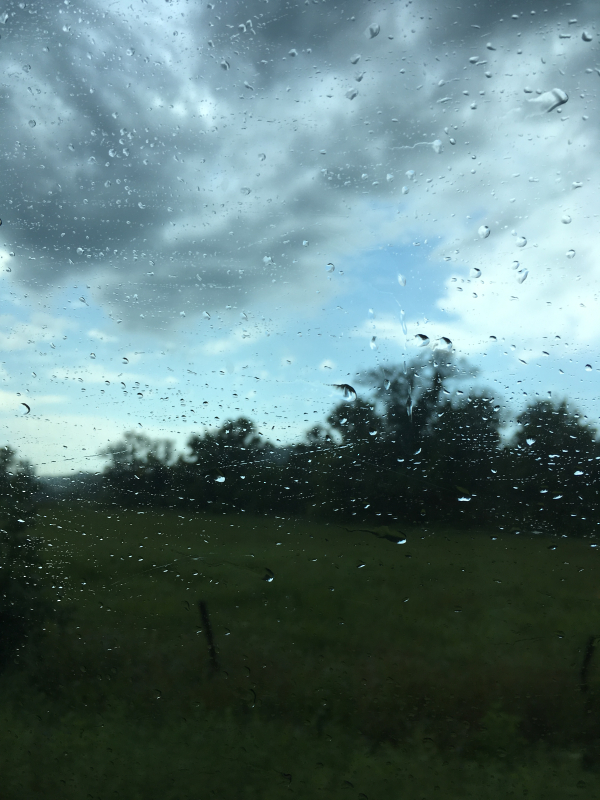

Rain poured and lightning flashed in the morning in Kansas City. We checked out of our hotel at 11 am and ran through the rain into a McDonald's, where patrons were watching the crescent sun on big screen teevees, a feed from the west coast where the eclipse had already started.

One hour and forty-five minutes to totality.

The parking lot was flooding and the sky was leaden. "At least we got to eat Kansas City barbecue last night," I was saying. I was tense. I had dragged the whole family down here for nothing.

Mark said: "We'll check the weather radar and drive towards clear skies."

I said: "There will be traffic jams. Maybe we had better stay put and hope that the rain passes."

Mark grinned at me and said: "You know what this is? This is an adventure. This is a weather-dependent activity. I do these all the time." And in that moment, I realized that whether we saw the sun or not, it was going to be okay.

+ + +

Fifteen minutes later we were in the car. Mark was driving fifty miles an hour in the pouring rain, twisting left and right between fields of tall corn, and I had a phone in each hand: one displaying the static, zoomable map of the totality path, and one tracking our little pulsing blue circle along the back roads northeast of Kansas City. "Does this road go east?" Mark was saying. "The skies are clearer to the south, but the car says it's going east."

One hour and twelve minutes to totality.

"It goes southeast," I repeated through the thunder of the rain on the roof of the car.

"The car is going east–"

"It zigzags. On average, it's southeast. We have to stay on this road to cross the river."

Our oldest, from the back seat, with a third phone open to live weather radar: "After we cross the river we need to cut west."

"West? Really?"

"West! After we cross the river."

Sixty minutes to totality.

There was a patch of blue sky, and Mark made for it. Amazingly, there were not a large number of cars on the road with us.

We came out of the rain.

Fifty-three minutes to totality.

"GO GO GO" I typed into Facebook. A friend under blue skies in Tennessee replied: "It's like Twister in reverse." It was. We were chasing the edge of the storm from the inside. I documented our location (Lexington, MO):

Forty-three minutes to totality.

Blue skies were ahead.

+ + +

"Let's stop here."

"We've got time."

"Look, there's space at this crossroads."

"We can get farther."

And then we passed a little driveway into a pasture, with a little chained gate a few yards from the road, and a pond on the other side of the gate, and Mark said: "That's where I'm going to stop. He pulled into the driveway of a bed and breakfast that was the next mailbox down, turned around, and went back to the little driveway and pulled in.

I got out of the car and I saw my shadow:

Twenty-five minutes to totality.

The sky.

+ + +

We set up telescopes, and pulled out our eclipse glasses embedded in paper plates for safety, and I looked up at the crescent sun and I realized that it was really going to happen. The children were positively leaping.

We put the three-year-old in the van for safety's sake, partly so he would not look at the sun, but mostly so he would not wander into the road. And we looked up, and stopped taking photos, and waited.

We felt it get cooler. We saw the light going all wrong, and I saw Mark laughing: "This light is crazy!"

"It's like a tornado sky," said my daughter. I agreed, it was like that.

The crickets began to sing. The children exclaimed over the shadow bands rippling in the road. I stood next to the van door so that I could keep some attention on the three-year-old. I watched the crescent get smaller through the eclipse glasses. This was so interesting that I forgot to look around at the deepening sky, or look to see the great shadow coming. I watched through the eclipse glasses until the light was completely gone and the children started shrieking. Then I looked.

+ + +

I had known what was going to happen. And… I had not known. What happened to me was this:

I staggered backward, two, three, steps, staring at the sky. I'm not sure if I was recoiling, or backing up to try to take it all in — either way, something crazy that couldn't make sense, because there is no way to get farther from the sky. "Oh, my God," I was saying, over and over again.

Yes, I could see the corona, ghostly in the blackness, and Venus down and to the right. Yes, I could see the ruby-colored sparkles around the black disk of the moon. Yes, it was beautiful.

It was not like seeing the tide rise and fall according to the tables. It was not like knowing that general relativity had been proven correct. It was just like the photographs, and yet it was nothing like the photographs. It looked just like the photographs, but standing there between a pasture and a cornfield, in the chilly midday of August, was not

I know some people say that it was like a religious experience. It was not like that for me. A religious experience is a sense of communing with the supernatural. I am kind of familiar with those, oddly enough. This was new. It was a natural experience. And it was making tears well out of my eyes.

"Oh, my God," I kept saying. My 13-year-old son kissed me on the cheek. I became aware of someone standing close behind me, grasping my bare upper arms in his warm hands. I remember deciding that it was probably Mark, but I could not tear my eyes away from the moon and the sun.

+ + +

The first thing I came up with to try to explain the experience was: Have you ever seen videos of audiences from the Beatles' tour of the U. S. in 1964? The young women weeping and dropping to their knees upon catching sight of the stars? I always wondered what on earth would make people act like this. But having seen the eclipse, I think it was a little bit like that, an extremely nerdy celebrity sighting. I am a science nerd. It is essential to my being. Total solar eclipses are celebrities, rare celebrities, a thing that I thought was tame but that has tamed me, apprivoisé, a thing I know like an old friend, like Fibonacci's sequence, like the digits of pi, like the hydrogen atom.

And there it was right in front of me! A thing I'd hoped to see for my whole life, but not ever allowed myself to long for, because maybe I would never attain it. And now I was face to face with it, and I knew — knew – it was something worth longing for. Had always been. And I was, in fact, weeping at the sight, and my knees really were weak.

+ + +

You can study the biology of human gestation for your whole life, become an expert, do original research, earn a medical degree, a Ph. D., see patients, weigh evidence, make predictions, feel the satisfaction of measuring the outcomes and watching them come true. Knowledge is valuable. And yet: it is not a substitute, never can be a substitute, for bringing your own child to birth. It's not the same.

You can know everything that's going to happen, and everything can progress exactly as you expect, and then experience knocks you back, with something you didn't even know was there, something beyond knowledge, something that ties you to every other human on the planet who has ever experienced the thing, and forever separates you from those who haven't.

And they don't know either, any more than you did, in the time before.

+ + +

The second thing I came up with to describe the experience was: It was less like an event than it was like a feature, like the mountains and the sea are features of our planet, but this is a feature of the solar system instead, the first feature I ever really got to see. Oddly enough, the starry night sky seems also to be a feature of our planet; even though it is located outside the planet, it looks the same all the time; we can look in different directions from here, but the view is essentially the same. The planets moving against the sky is a little like this, but you cannot really watch it happen because it is too slow.

Our planet has some very beautiful features. Before Monday I often said that the most beautiful place I have ever been is the Alps above the Chamonix Valley; I said that the first time I went there when I was in college, and I said it again when I returned with my husband and five children twenty years later. I have seen and heard other beautiful features: certain birds and jellyfish, certain beaches at sunrise, certain echoes of laughter ringing in columned arcades, certain cleverly shaped and polished stones. The total solar eclipse is like that: a thing worth traveling to see, all by itself, but it's not of this earth, it's of something larger, it's of the sun and all its orbiters, including me. The limited slips of time in which it happens, well, that's just part of the directions to get there, they're simply directions that include both time and space.

I will be back in the Alps very soon, and I somehow think it will no longer be the most beautiful place I have ever been.

+ + +

If there's one thing I perceive intellectually more than I did before, it's the tremendous gift given to us at the formation of the solar system, the gift of a moon that is, sometimes, the same size in the sky as our sun. Much larger or closer and it would cover up the corona; much smaller or farther, and we would never have totality. It did not have to be that way, and it is, for no particular reason; it just is. A gift. Everything that is beautiful is a gift, but knowing it increases its beauty.

I knew that, but I know it more now, and I am truly grateful.

+ + +

It was over fast, and the light came back, and the shadow bands were streaming over the road, like the shadows of clouds, but impossibly fast. And we threw everything in the car and raced to beat the traffic going home on I-35.

The memory of those two minutes and nine seconds is truly dreamlike; I remember the feeling, the shock, the staggering backwards, the tears, reaching my hand out to the van to steady myself. One of the strangest parts of the memory is the way I realized that Mark was standing behind me and holding me: that I hadn't even noticed him coming up to me and putting his hands on my arms, the way he seemed to came out of nowhere, the way I had become aware of that sensation without really being aware of what it meant, or who he was, or thinking, really, about anything at all.

Astonishment. Pure astonishment, and a sight, and even now I can barely remember the sight, but in a breath I can remember the way the astonishment took hold of me. I can relive it, sometimes, not by watching videos of the sun disappearing, but by hearing audio of the crowds gasping and stammering, the way I gasped and stammered.

Will it happen again, if I travel to see another one?

I don't know. I will find out, I hope, in 2024.