This is the third in a series of post in response to a reader’s request, asking me to write about the “lack of scientific evidence for the divine,” from the perspective of a “scientifically-minded” individual who began Church practice as an adult.

In the first post, I offered a working definition of “scientific evidence” and explained why I wouldn’t expect there to be any such evidence for the divine anyway. In my second post, I considered why a so-called “scientifically-minded individual” would be expected to be less likely to become a believer. In that post I suggested that it is less a matter of such individuals coming to belief in a special, er, scientifically-mnded way, than it is a matter of finding a way around particular obstacles to accepting the possibility of the divine.

In this post, I want to describe three fundamentally different ways that the scientist who is also a believer deals with the lack of scientific evidence for the divine.

+ + +

1. “What lack of scientific evidence? I see scientific evidence for a Creator everywhere.”

In my first post, I wrote that I, personally, do not believe that there is any scientific evidence for the divine, and in fact I don’t expect that there ever will be any.

But that’s me.

You will, of course, find people with scientific or technical training who are deeply impressed by the mathematical laws of the universe, or the structure of the human eye, or the workings of the transformation of species. They see the handiwork of the Designer there.

I would not call this “scientific” evidence. What I would call that is an intuitive reaction to realities that required a scientific or technical education in order to fully appreciate. Perhaps you could fairly characterize it as an accumulation of apparently supporting evidence, or at least of evidence that fails to argue against the divine.

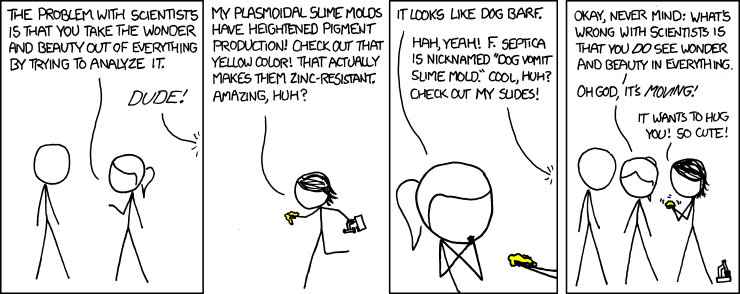

Maybe xkcd captures the spirit I’m talking about best:

Just substitute “evidence for the divine” for “wonder and beauty” and that is pretty close to what we’re talking about.

In this category you could also include any people who are seriously into the various philosophies that fit under the umbrella of “intelligent design.” I confess that I am not very current on the details of what the philosophical leaders (as opposed to the political leaders) of the ID movement are discussing right now. It strikes me that the fundamental philosophical prerequisite is twofold:

- It is possible that a rational being created the laws of the universe, and it cannot be proved otherwise;

- The benefit of the doubt is given to the proposition “There is a God who created the laws of the universe,” and it is the opponents who must prove their case.

The latter is arbitrary and, I think, largely a matter of personal non-rational processes. There is nothing wrong with the yes-to-God proposition, from a purely philosophical standpoint. But there is really no arguing for or against it in a purely logical way. Some people (scientists or no) think it better to give the benefit of the doubt to the no-God proposition. Some refuse to give it to either.

2. The philosophical approach: Evidence from within the interior experience of the human person.

Just because a person is a scientist or an engineer or a technician or a computer programmer or an applied mathematician does not mean that she necessarily subscribes to the “scientific evidence is the only important kind of evidence” view. Pure philosophy, in other words, is accessible to logical thinkers whether or not they possess particular scientific interest or expertise.

Besides the kind of evidence that can be reproduced experimentally or demonstrated to others, so that those others may directly evaluate them, every human being has access to a certain set of direct observations which cannot be demonstrated or reproduced to others. To the individual, they are experienced as reality, even though they cannot be transferred.

I’m speaking here of observations of one’s own powers of reason and insight, or of the existence of an internal moral code.

A fact that is unappreciated in our society: There is absolutely no way you can derive a moral conclusion, a “what ought to be done,” from purely natural knowledge (“what is”) or from technical expertise (“what could be done”). Scientific and technical expertise is immensely useful in contributing to the discussion of “what ought to be done,” because knowledge of what is, and knowledge of what could be, is relevant to narrowing down the choices: that kind of expertise helps us predict the likely consequences of our actions. That is why it is useful to have specialists in scientific and technical fields on policy committees. But even if the consequences of our likely actions could be perfectly predicted by the technical experts, and perfectly explained by them to the public at large. we are still left with the question of which consequences ought to be preferred. And that question belongs to all humans, not just to the ones with technical expertise.

I look inside myself and I see a moral code. Other people tell me that they look inside themselves and see moral codes (they can’t prove it to me, but for the purpose of this argument I will assume they are not lying). It is in this personal moral code that many people are forced to conclude that they really do believe in free will, in the existence of “right” moral decisions and “wrong” ones, and through a philosophical chain of reasoning conclude that all this must be discarded unless the proposition “God exists” is accepted. Not wanting to discard the propositions that the will is free and that certain decisions are right and others wrong, they choose to accept the “yes to God” proposition.

A basic outline of this essentially philosophical basis for the “yes to God” proposition can be found in the opening pages of C. S. Lewis’s popular work Mere Christianity. (“Look inside” the book and you’ll get the gist of it. There’s nothing about being “scientifically minded” that would make a person any more or less likely to accept Lewis’s argument, as it’s accessible through propositions and logic, not through technical expertise. Whether the propositions are accepted or not is, I think, personal.)

A different interior observation on which to found belief in a Deity could be observation of the self’s powers of reason. I know that some have argued that rational thinking (which can’t be demonstrated or transferred, only observed within the self) must arise from rational, not irrational processes. I haven’t explored this line of thinking myself; but I know others who have.

This category of “interior, personal human experience” could also refer to a person who believes he has received a personal communication or revelation from God. Ultimately, this too is an interior experience (in the sense that it cannot be shared directly with others). It can’t be transferred. And yet the individual who is confident in its authenticity has what can be called direct experience that, depending on its strength, could easily trump all arguments.

+ + +

3. Historical evidence.

</p?

+ + +

But if you take anything at all away from this post, it should be that there is nothing particularly new, or even modern, about the believer who is also a scientist. Mendel was a friar, remember? (The monastery’s experimental garden had been producing research results long before he got there.) Copernicus was a priest. Look, here’s a whole list.

And there are many other places to look for an understanding of what thoughtful believers are writing about the reasons for their faith. Here’s a blog with a philosophical approach; the link goes to a sample post about original sin and modern biology. Here’s a blog about science and the Catholic faith with many posts relevant to this topic. Of course, if you want a sobering reminder that these questions have been carefully considered for a long time, you could delve into Summa Theologica: Prima Pars. (And remember that St. Tom turned out to be correct about that whole “yes, the universe has a beginning” thing.)